Perception vs. Reality

Feeling lucky has less to do with lottery tickets and more to do with mindset. It’s not about odds it’s about interpretation. Think of luck not as an event, but as a lens. Two people can walk into the same situation say, a delayed flight. One sees wasted time and inconvenience. The other finds a chance to reflect, meet someone new, or finally read that book. Same moment. Different meaning.

That’s what makes luck slippery. It isn’t fixed; it’s filtered. The brain constantly edits what we notice and how we frame it. Our sense of luck is shaped by awareness. Where your attention goes, your meaning follows. And meaning is everything when it comes to how ‘lucky’ an event feels.

This doesn’t mean luck is imaginary. It means it’s personal. What counts as a fortunate break to one person may barely register for another. In that way, luck is less about chance and more about what your brain is ready to see.

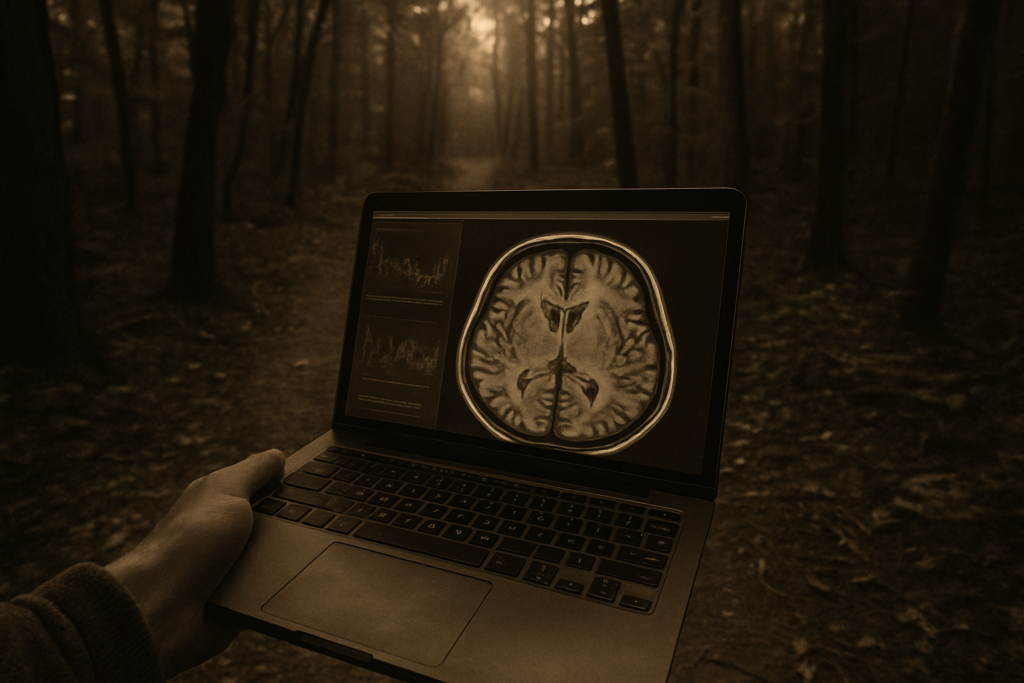

The Brain’s Role in ‘Lucky’ Thinking

The idea of luck isn’t just storybook fluff your brain has skin in the game. It starts with the prefrontal cortex, the part of your brain in charge of focus, judgment, and decision making. Think of it as the editor on duty, filtering incoming noise and spotlighting what matters. If you’re dialed into looking for opportunity, your prefrontal cortex helps you catch it. If you’re zoned out, you might walk right past your next big break without even seeing it.

Dopamine the brain’s chemical hype man plays a major role too. It sparks optimism, boosts motivation, and increases your sensitivity to rewards. People with naturally higher dopamine activity tend to expect good outcomes, which nudges them to take chances and follow through. That creates a feedback loop: expect more, try more, get more.

Then there’s pattern recognition. This is your brain’s instinct to link events, spot sequences, and make meaning from randomness. If you feel lucky, it might be because your brain is especially good at noticing outcomes that fit your narrative. It’s a built in detector that tells you, “Hey something good just happened again.” And over time, it helps reinforce the belief that good things just seem to happen to you.

Turns out, “luck” might be more about mental wiring than magic.

The Attention Bias Effect

People who describe themselves as lucky don’t usually win more lotteries or dodge lightning more often. What they do, though, is notice chances most others overlook. They walk into a crowded room and somehow find the one person who’ll boost their career. They act on a hunch and land a perfect opportunity. It’s not mysticism it’s selective attention.

Our brains filter a massive amount of sensory input every second. What gets through depends on what you expect to see. If you believe things work out for you, your mind is primed to notice positive cues open doors, friendly faces, out of the blue emails. This is called the attention bias. It organizes chaos into a story that makes sense to you and if your story involves luck, the brain reinforces that belief by highlighting confirming evidence.

On a neural level, it comes down to expectancy. The brain is constantly predicting what will happen next. That predictive coding system relies heavily on past experiences and beliefs. If you expect things to go well, your brain scans for congruent data. This in turn shapes your behavior maybe you smile more, take more risks, follow leads others ignore. The loop feeds itself.

So luck, it turns out, is less about what happens to you and more about what your brain chooses to see. Expect something good and you’re more likely to notice it when it shows up.

Rewiring for Luck

Feeling lucky isn’t about superstition it’s about how your brain filters what’s worth noticing. The good news? You can train it.

Start with potential wins. Most people scan for problems; lucky thinkers scan for openings. That’s not rose colored glasses it’s a practiced shift in mental focus. Instead of asking, “What might go wrong?” start asking, “What good could come out of this?” The brain follows the questions we repeat. Train it to explore upside instead of bracing for downside.

Gratitude and cognitive reframing are also heavy hitters. Gratitude nudges your attention toward what’s already working. Reframing helps flip situations to reveal hidden value: a delay becomes breathing room, a loss becomes learning. This isn’t about denying problems. It’s about choosing where to linger.

Last piece of the puzzle: take care of your brain’s chemistry. Sleep, food, and mood all tweak how you perceive reality. Low sleep? Your brain’s more likely to register threats than opportunities. Junk food? Can dull dopamine response. Chronic stress? Narrows thinking. In short how you feel shapes how lucky things seem.

Changing your luck begins with how you look at life. Your odds improve when your focus does.

Supported by Psychology

Bridging Brain and Behavior

Neuroscience gives us insight into how the brain processes information, but psychology helps explain how those processes influence mindset and behavior. The feeling of being lucky often stems from specific thought patterns and beliefs many of which are shaped over time and can be intentionally adjusted.

Key Cognitive Theories at Play

Several well supported psychological concepts align with what we’ve observed in neural findings:

Cognitive appraisal theory: The way we interpret events, not the events themselves, largely determines how we feel about them. People who feel lucky tend to appraise ambiguous situations more positively.

Confirmation bias: Once someone believes they’re lucky, they begin to unconsciously seek evidence that supports that belief and overlook evidence that doesn’t.

Attribution theory: Individuals who attribute positive outcomes to internal causes (like their own persistence or intuition) are more likely to see themselves as lucky.

Learned Optimism and Self Efficacy

Two foundational psychological skills also play a strong role in shaping a lucky mindset:

Learned optimism: Coined by psychologist Martin Seligman, this concept is about training yourself to see setbacks as temporary and specific not permanent or all encompassing. Optimistic individuals are more likely to notice hidden opportunities even in negative situations.

Self efficacy: Your belief in your own ability to affect outcomes. High self efficacy not only motivates action but can actually influence how the brain responds to challenges, helping you stay engaged and more open to chance encounters or surprises.

Want to Go Deeper?

For a deeper dive into these psychological principles and how they relate to feeling lucky, check out: Psychology of Luck

Takeaway: You Can Build a Luckier Brain

Luck isn’t chance it’s a mindset built over time. Neuroscience tells us that the people who seem to “have all the luck” are often just wired to spot it when it shows up. Their brains are trained to notice patterns, lean into the positive, and stay mentally ready for opportunity.

Of course, this isn’t a magic trick. It’s about practice. With the right habits like reframing setbacks, staying grateful, and directing attention toward potential wins you can shift your mental default. This strengthens neural pathways that make you more aware, more responsive, and yes, more “lucky.”

It’s not about chasing luck. It’s about becoming the kind of person who recognizes it and takes action. You can literally train your brain to get better at catching breaks. And that’s more powerful than hoping for lightning to strike.

Dig deeper into how this works: Psychology of Luck

Archer Loftus-Hills played a pivotal role in shaping the technical backbone of Gamble Today Smart. With a keen eye for detail and a passion for innovation, Archer was instrumental in developing the platform’s data-driven tools and analytics features. His expertise ensured that users could access reliable, real-time insights to make informed gambling decisions. Archer’s dedication to precision and functionality has left a lasting impact on the platform’s success.

Archer Loftus-Hills played a pivotal role in shaping the technical backbone of Gamble Today Smart. With a keen eye for detail and a passion for innovation, Archer was instrumental in developing the platform’s data-driven tools and analytics features. His expertise ensured that users could access reliable, real-time insights to make informed gambling decisions. Archer’s dedication to precision and functionality has left a lasting impact on the platform’s success.